An analysis of the bones found in South Africa suggests Australopithecus sediba is the most likely candidate to be the ancestor of humans, said lead researcher Lee R. Berger of the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa.

The fossils, belonging to a male child and an adult female, show a novel combination of features, almost as though nature were experimenting. Some resemble pre-human creatures while others suggest the genus Homo, which includes Homo sapiens, modern people.

"It's as if evolution is caught in one vital moment, a stop-action snapshot of evolution in action," said Richard Potts, director of the human origins program at the Smithsonian Institution. He was not among the team, led by South African scientists, whose research was published online Thursday in the journal Science.

Scientists have long considered the Australopithecus family, which includes the famous fossil Lucy, to be a primitive candidate for a human ancestor. The new research establishes a creature that combines features of both groups.

The newly studied bones were found in 2008 in the fossil-rich cave region of Malapa near Johannesberg. Berger's then 9-year-old son, Matthew, found a bone that was determined to belong to the child. Two weeks later Berger uncovered the fossils of the female.

The journal published five papers detailing the findings, including separate reports on the foot, hand, pelvis and brain of A. sediba.

Berger said the brain, hand and foot have characteristics of both modern and early pre-human forms that show a transition under way. It represents a bona fide model that could lead to the human genus Homo, Berger said.

Kristian J. Carlson, also at Witwatersrand, said the brain of A. sediba is small, like that of a chimpanzee, but with a configuration more human, particularly with an expansion behind and above the eyes.

This seems to be evidence that the brain was reorganizing along more modern lines before it began its expansion to the current larger size, Carlson said in a teleconference.

"It will take a lot of scrutiny of the papers and of the fossils by more and more researchers over the coming months and years, but these analyses could well be `game-changers' in understanding human evolution," according to the Smithsonian's Potts.

So, does all this mean A. sediba was the "missing link"?

Well, scientists don't like that term, which Berger calls "biologically unsound."

This is a good candidate to represent the evolution of humans, he said, but the earliest definitive example of Homo is 150,000 to 200,000 years younger.

Scientists prefer the terms "transition form" or "intermediary form," said Darryl J. DeRuiter of Texas A&M University.

"This is what evolutionary theory would predict, this mixture of Australopithecene and Homo," DeRuiter said. "It's strong confirmation of evolutionary theory."

But it's not yet an example of the genus Homo, he said, though it could have led to several early human forms, including Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis or Homo erectus – all considered early distant cousins to man, Homo sapiens.

These articles "force a rethinking of how traits are coupled together in human evolution," the Smithsonian's Potts said in an email from Kenya, where he is doing research.

"For example, in previous definitions of our genus, the leading edge in the emergence of Homo has been brain enlargement. The sediba bones show, however, that reorganization of the brain and pelvis typically connected with the evolution of Homo need not have involved brain enlargement," he noted.

"The more we learn about human evolution, the more we see that traits" that must have happened together could occur separately, Potts said.

For example, the study of the hand shows that major changes in the thumb usually associated with toolmaking "did not imply abandoning life in the trees. In the foot article, we're introduced to a unique and previously unknown combination of archaic and advanced traits in sediba," Potts explained.

The researchers reported that the fingers of A. sediba were curved, as might be seen in a creature that climbed in trees. But they were also slim and the thumb was long, more like a Homo thumb, so the hand was potentially capable of using tools, though no tools were found at the site.

The fossil provides the first chance for researchers to evaluate the function of a full hand this old, said Tracy Kivell of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany. Previously, hand bones older than Neanderthals have been isolated pieces rather that full sets.

The heel bone seems primitive, the researchers said. Yet its front is angled, suggesting an arched foot for walking on the ground, and there is a large attachment for an Achilles tendon as in modern humans, they said.

The pelvis is short and broad like a human pelvis, creating more of a bowl shape than in earlier Australopith fossils like the famous Lucy, explained Job Kibii of the University of the Witwatersrand.

That may force a re-evaluation of the process of evolution because many researchers had previously associated development of a human-like pelvis with enlargement of the brain, but in A. sediba the brain was still small.

The name Australopithecus means "southern ape," and "sediba" means natural spring, fountain or wellspring in the local Sotho language.

After the bones were discovered, the children of South Africa were invited to name the child, which they called "Karabo," meaning "answer" in the local Tswana language. The older skeleton has not yet been given a nickname, Berger said.

The juvenile would have been aged 10 to 13 in terms of human development; the female was in her 20s and there are indications that she may have given birth once. The researchers are not sure if the two were related.

___

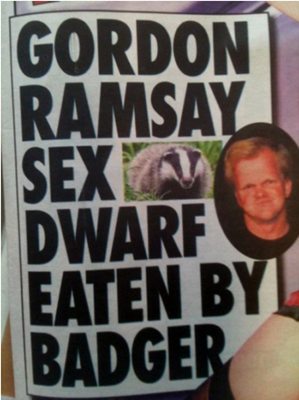

A coup of tabloid headline writing, from the UK rag The Sunday Sport. The backstory, from BuzzFeed:

A coup of tabloid headline writing, from the UK rag The Sunday Sport. The backstory, from BuzzFeed:

Glad you asked

Glad you asked