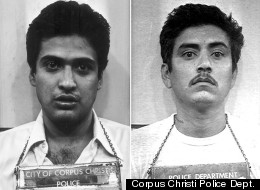

Carlos DeLuna (left) and Carlos Hernandez

Carlos DeLuna was executed in 1989 for stabbing to death a gas station clerk in Corpus Christi six years earlier. It was a ghastly crime. The trial attracted local attention, but not from concern that a guiltless man would be punished while the killer went free.

DeLuna, an eighth grade dropout, maintained that he was innocent from the moment cops put him in the back seat of a patrol car until the day he died. Today, 29 years after DeLuna was arrested, Liebman and his team published a mammoth report in the Human Rights Law Review that concludes DeLuna paid with his life for a crime he likely did not commit. Shoddy police work, the prosecution's failure to pursue another suspect, and a weak defense combined to send DeLuna to death row, they argued.

"I would say that across the board, there was nonchalance," Liebman told The Huffington Post. "It looked like a common case, but we found that there was a very serious claim of innocence."Police and prosecutors treated the killing of Wanda Lopez at the Sigmor Shamrock gas station on February 4, 1983, like a robbery gone bad. A recording of the chilling 911 call from Lopez, a 24-year-old single mom working the night shift, captured her screaming and begging her killer for mercy.

DeLuna, then 20, was found hiding under a pickup truck a few blocks from the gory crime scene. A wad of rolled-up bills totaling $149 was in his pocket.

Eyewitness testimony formed the bedrock of the case against him. Now, that testimony is perhaps most contested aspect of his conviction.

Cops brought DeLuna back to the Shamrock. A customer filling his tank before the murder told police that DeLuna was the man he saw putting a knife in his pocket outside the store. Another customer who rushed to the store's entrance when he heard Lopez struggling identified DeLuna as the man who emerged. A married couple saw a man running a few blocks away and later identified DeLuna in police photos shown to them.

With DeLuna's record of numerous arrests for burglary and public drunkenness, plus a conviction for attempted rape and auto theft, it seemed like police had found the perp. But Liebman said DeLuna took the fall in a case of mistaken identity.

Among the key findings in the Columbia team's report:

- The eyewitness statements actually conflict with each other. What witnesses said about the appearance and location of the suspect suggest that they were describing more than one person.

- Photos of a bloody footprint and blood spatter on the walls suggest the killer would have had blood on his shoes and pant legs, yet DeLuna's clothes were clean.

- Prosecutors and police ignored tips unearthed in the case files that Carlos Hernandez, an older friend of DeLuna, who had a reputation for wielding a blade, had killed Lopez. The defense failed to track down Hernandez, who bore a striking resemblance to DeLuna.

"If a new trial was somehow able to be conducted today, a jury would acquit DeLuna" said Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, who read a draft of Liebman's report. "We don't have a perfect case where can agree that we have an innocent person who's been executed, but by weight of this investigation, I think we can say this is as close as a person is going to come."

In 1983 and during the appeals process, officials handling DeLuna's case saw the opposite -- a slam-dunk conviction. The prosecution and the court-appointed defense lawyer didn't put much stock in DeLuna's claim that Hernandez plunged a knife into Lopez's chest. Record-keeping was so lax there's no clear evidence the gas station was robbed during the slaying, Liebman said.

In trying to clear his name, DeLuna didn't help himself. For months after his arrest, he refused to reveal the name of the real killer, because he feared Hernandez. His credibility plummeted when other parts of his alibi for the night of the murder were disproven by the prosecutor.

The fateful night began, according to DeLuna, when he went to a skating rink, where he met Hernandez and two sisters. DeLuna admitted that he was near the gas station later, but said he was across the street in a bar. While he nursed his drink, Hernandez bought cigarettes in the Shamrock. He said he emerged from the bar to see Hernandez fighting with Lopez. Hearing police sirens, he said he fled, because he didn't want to get into trouble.

The prosecution, however, discredited DeLuna's version of events. One of the sisters who was allegedly with him at the rink testified that she was at her baby shower that night.

"I had blown his alibi to bits," said Steve Schiwetz, one of the prosecutors.

A guilty verdict was reached with little delay. The capital murder trial lasted six days in July 1983.

"I'm open to the argument that somebody named Carlos Hernandez really did it," said Schiwetz, "but everything I know confirms the original impression that DeLuna did it."

The apparent random targeting of Lopez wasn't Hernandez's style, Schiwetz said. Hernandez's tendency was to unleash violence on the his girlfriends and wife, not strangers, he said. In 1986, Hernandez was accused of murdering another woman with a knife, but the case was dismissed.

Several of Hernandez' family members interviewed for the Columbia University report said pictures of the murder weapon found at the gas station looked like the knife Hernandez habitually kept with him. In all of DeLuna's numerous arrests, police never found him carrying a blade, according to the Columbia report.

The relatives' portrait of Hernandez's disheveled appearance gelled with a description of the suspect seen fleeing the convenience store. Witness Kevan Baker said the killer looked like a "derelict," wearing a flannel jacket and gray sweatshirt. Hernandez's relatives said he often wore a flannel coat. DeLuna was fastidious with his appearance and always wore black slacks and dress shirts, the report said.

Liebman sought more scientific proof. Fingerprints taken from the knife and cigarette pack found at the crime scene were sent to a former Scotland Yard investigator for comparison with Hernandez's prints. But the evidence had been so poorly collected by police, Liebman said, that the results were inconclusive.

The Columbia University team's report, more than 400 pages long, also is a biography of the central players, emphasizing the troubled upbringings and hard-drinking adulthoods of DeLuna and Hernandez.

Liebman learned about DeLuna roughly 10 years ago, when he began examining convictions in which a single eyewitness testified. As he and a student delved into the files, they became convinced DeLuna wasn't guilty.

They turned over their findings to the Chicago Tribune which published a three-part series in 2006 that found evidence suggesting Hernandez killed Lopez. Multiple people told the Tribune that Hernandez -- who died in 1999 in prison from cirrhosis of the liver -- had confessed to killing her.

Revisiting questions about Lopez's death would be too painful, her nephews said. "That's something our family has had to deal with," Louis Vargas told The Huffington Post. "We've had closure with it and we don't want to reopen it. We believe the justice system did what it had to do."

One of DeLuna's attorneys, James Lawrence, told HuffPost he doesn't count him among the clients who've been wrongfully accused of capital crimes.

"The fact that he wouldn't help us and this was his life on the line -- that's the one thing that kept bothering the living daylights out of me," Lawrence said.

Since the Supreme Court reinstated capital punishment in 1976, there have been 1,295 executions, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Texas leads with 482 executions.

The ease with which DeLuna was prosecuted and the obscurity of his death are what makes his case so important, said Liebman.

"There are many cases out there that nobody has ever looked at and are probably at risk of innocence," said Liebman. "It's a cautionary tale about the risks we take when we have the death penalty."

No comments:

Post a Comment